#6: The Leech Effect

It’s time to face up to the reality that, when a theory’s been proven not to work, it’s time to dump it, not keep on with it just because there isn’t a new one to follow.

If you don’t understand why countries can go bankrupt, why banks are deemed too big to fail, or why day traders make profits from goods that don’t even exist – you’re in good company. Our politicians are equally clueless. Opinions are offered from all sides, their common denominator being that nobody knows what will work or what will make the damage greater still. There is no new theory available to explain the situation, only followers of known theories. Theories never collapse under the weight of their own failure. They only collapse when a new theory comes along. While there isn’t one in sight we feel powerless. We do not like what not knowing feels like. We are no good at admitting our ignorance.

For years, American Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan was revered as a demi-god of financial knowledge. When in 2008 the financial markets collapsed Greenspan suddenly realised that he had been wrong and – unlike most politicians – he even admitted his failure. He told the Congressional Committee that ‘the whole intellectual construct collapsed’. Asked whether his view of the world, his theory, had been wrong, he simply answered: ‘Yes, precisely.’ He was referring to the theory of it being possible to steer the economy simply by controlling the amount of money in circulation. So we have it on record from a former authority that this theory does not work, and yet Western governments have been sticking with it. The only reason seems to be that no-one has offered an alternative, at least no-one with any authority.

For centuries, certain financial deals had worked without there being any theory at all. Long before economists had received the Nobel Prize for working out the exact mechanism behind derivatives and other options, these were being bought and sold at the Amsterdam stock exchange during the 1600s, what the Dutch call the ‘Golden Century’. They used most of the tricks still around today, albeit following common sense and their instincts. Easy enough, one could say, when there were only a few traders, they knew each other and news travelled at the speed of sailboats. In the 400 years since then though, things have become so complex that even traders admit that no one understands what is going on. Computer programs decide what will be a profitable deal and when to make it. The slightest hitch will throw the whole complex, interconnected machinery into chaos. We have seen that and still no one will admit that the system is not sustainable.

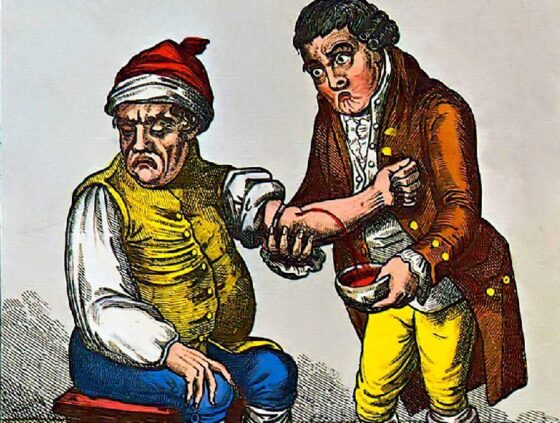

This lack of admitting ignorance in view of the overwhelming evidence as to the failure of the system reminds me of the good old medical practice of bloodletting. Not because I would compare modern bankers with leeches – I wouldn’t dare! – but because that practice went on for centuries without the slightest shred of evidence that it brought any benefit to the poor patients. It was based on an ancient theory and it lasted so long because a new one hadn’t come along. Well into the 19th century letting blood was based on the humoral theory which proposed that, when the four humours – blood, phlegm, black and yellow bile – in the human body were in balance, good health was guaranteed. An imbalance in the proportions of these humours was believed to be the cause of ill health.

Bloodletting was supposed to redress the balance. A man comes to the doctor who cuts open the artery on the patient’s lower arm and drains about a pint of blood. The man faints but will have to go through this procedure another five times, after which he lies on his bed with six deep cuts in his arms and pretty much half-dead. Now the doctor puts leeches on to the wounds which slowly suck out more blood. When they’re full until they almost burst, they are replaced by hungry new leeches. This goes on for six weeks or more until the patient is released – if he isn’t dead by then. For centuries the medical establishment had noticed that most patients did much better without having leeches administered. But they didn’t have a better theory, so they stuck with a practice that was ludicrous and outright dangerous. The humoral theory is a striking example for all theories that deal with complex systems, be it the human body, cities, war, eco-systems, companies or the financial system. We do not give up a wrong theory when it has proven to be wrong, but only when a new one has come along. That may not be rational behaviour, but it seems to be prevailing. Let’s call it the Leech Effect.