#30 Blandification

When I read about the J&J rebranding, I simply couldn’t stop myself from writing a comment. Little did I know that my short note would cause so many people to add their own comments. Even one year later, LinkedIn still sends me more comments – time to publish my little rant here.

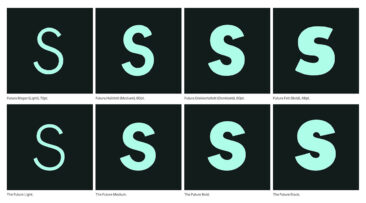

I’m so fed up with marketing people running projects without acknowledging that we designers might have an idea or two about what communicates and what doesn’t. They’ve been told by tech guys and lazy web-designers that things have to be simplified to work on screens. This is knowledge from the 90s and not true anymore. Risk and guts have been replaced by bullshit “narratives” invented by people who’ve never taken a risk in their lives. This is the blandification of our world, where fun has to be taken out of the equation because it cannot be quantified. No consumer cares about a company’s internal reorganization, they want to like a brand. When all brands are beige, the beigest one will not win, but will be forgotten. The enshittification of our world is run by people who read spreadsheets in bed and look at their smartphones to tell the weather instead of sticking their heads out of the window.

Sometimes I’m glad that I am old and don’t have to take orders from gutless employed managers anymore. My best clients were those I could argue with. It wasn’t about winning or being right, it was about doing the best work.

Thank you Adobe, Audi, VW, Mercedes, Deutsche Bahn, BVG, Bosch, Ottobock, The Economist, wdr, zdf, FontShop, Gravis, Tegut, Messe Frankfurt … and all the other clients I worked with, not just for.

The word enshittification was coined by Cory Doctorow @doctorow.

★