#21 Typography: History and Technology

Before the invention of writing, men lived in an acoustic world, left to their dark thoughts.

Mankind was only freed from its ignorance with the invention of writing.

The goose quill meant that speaking had an end, as Marshall McLuhan put it. Mystery was abolished, now there were buildings and cities, streets and armies, bureaucracy. Civilization began, the step from the darkness of prehistory into the light of consciousness.

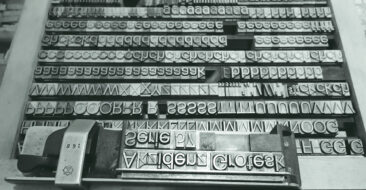

The invention of movable type was the next major leap in the development. What up until then an individual could only write once, or at best chisel in stone, was now applicable anywhere and everywhere. The separation of action and function was the condition for most of the developments of the modern age; individualism, democracy, protestantism, capitalism, and nationalism. The technology of printing and typesetting has fundamentally altered our habits of perception.

The general term typography refers to the functions of typeface design and the arrangement of type and other elements on a page. This page can also be a computer screen or the wall of a building. Up until the introduction of mechanized typesetting, compositors were the only typographers: they were also responsible for designing the pages.

The history of typography is both a history of technology and of culture. Each technical development left its trace in design and in the typographic layout. The classification of typefaces employs the same descriptions as the ones we use for stylistic periods in architecture.

Printing using movable characters originated in China in the early 11th century. The characters were made of clay, and thus not particularly durable. 200 years later in Korea entire pages were cut in wood or cast in metal. Although this meant type was reproducible, each page could only be used once. It was the goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1398 – 1468) who first had the idea of cutting single letters as steel punches. These were stamped into metal to make moulds, which, in turn, were filled with a soft metal. Working in Mainz, around 1450, Gutenberg also developed the tools for type founding, which remained in use almost unchanged until the mid 19th century, and the first printing press. It consisted of a screw press, like those used to press grapes. The thin liquid inks which had been used to print wooden panels weren’t right for printing lead characters. Gutenberg had to invent an emulsion using linseed oil and soot which was sufficiently thick and dried quickly. Each sheet of paper had to be inserted and removed by hand. It wasn’t until 1814 that the Times became the first newspaper in the world to be printed on a steam-powered press made by the German mechanics Koenig & Bauer, allowing the production of up to 1100 copies per hour. Twenty years later the industrial manufacture of type using casting machines would also become a practical reality, culminating in the introduction of the Linotype machine in 1886, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler (1854 – 1899). This machine produced lines of type (!) for newspapers and book publishers. It survived in various forms into the 1970s, when it was replaced by photosetting machines.

Gutenberg’s first printed bible was an attempt at imitating the contemporary style of handwriting without making the mechanical origin of the print obvious. He cut several hundred ligatures that made it possible to set each line at the same width so that the reading flow would not be interrupted by varied word spacing. The type used in the Gutenberg bible was the narrow, steep Gothic script. In Germany tall, narrow Gothic arches were being built, whose shapes were reflected in type. However, in Italy the shapes of the Renaissance were already predominant.

The punchcutters in Italy of the late 15th fifteenth century, such as Nicolas Jenson (1420 – 1480) or Aldus Manutius (1449 – 1515), based the design of their lowercase characters on the cursive humanistic minuscule. Due to their geographic and historical origin they’re classified as Venetian Renaissance Antiqua. Like it still is to this day, the uppercase was modelled on the unrivalled Roman Capitalis, as represented on the Trajan column in Rome. Named after a cardinal, Bembo (ca. 1495) by Aldus Manutius and his punchcutter Francesco Griffo (1449 – 1518) marks the end of the development and is the prototype for Renaissance Antiqua of Italian origin. It took several centuries for the cursive forms to be integrated into complete type families. To this day they are known in English as Italics.

The most famous representative of the French Renaissance Antiqua was the Parisian punchcutter Claude Garamond (1499 – 1561). He and his contemporary Robert Granjon (1513 – 1589) are the originators of the typefaces described as Garamonds which became the most common book faces around 1600, which they remain today.

At the beginning of the seventeenth 17th century the Netherlands became the centre for type founding. The types at the height of the Baroque period are more casual, more robust and therefore more functional than the Renaissance typefaces. Towards the end of the 17th century punchcutters were becoming increasingly influenced by the shapes of contemporary copper engravings. The contrast between stem and hairline became more pronounced, letters looked more clinical, their shapes more precise. The punchcutters’ work was deeply influenced by Cartesian thinking and improved tools for punchcutting and type founding, in addition to higher quality paper available for setting, thanks to superior printing machines. The typefaces of William Caslon (1692 – 1766) represent the peak of this development. His designs may not be particularly innovative or original but so pragmatically British that they soon spread successfully. Britain’s expansion as a colonial power certainly helped the matter, leading to the very Declaration of Independence of the United States of America actually being set in Caslon. The end of this period is marked by John Baskerville (1706 – 1775), a skilled tombstone engraver in Birmingham who greatly influenced the classical typeface designers with his type, rich in contrast and itself influenced by copper engraving.

Classicism in typography, as in architecture, was never very inclined toward luxurious adornment. The ideals of the Enlightenment also required clarity and generosity of typography. Symmetry and reduction were the overriding principles of design. Thanks to the ability to print larger forms with higher precision, books became bigger (the first all-iron Stanhope press was built in 1800). Technology allowed serifs to be designed very delicately and express a lot of detail in the characters. Constructing letters with compass and ruler may have led to the desired ideal shapes, but the typefaces were actually harder to read than their Renaissance and Baroque predecessors.

Giovanni Battista (‘Giambattista’) Bodoni (1740 – 1813) was called the King of Printers and Printer of Kings. Bodoni devised and cut 270 different alphabets, for which he had to engrave some 55.000 steel punches by hand. Critics have described Bodoni’s typefaces as the expression of feudalism, even though most of them were created long after the French Revolution. He stayed away from politics, although his books were kept in Napoleon Bonaparte’s own private library. There was, however, criticism of Bodoni’s typefaces at the time – particularly in France where he had competitors who deemed themselves sole representatives of classicism in typography. The English artist, draughtsman, type designer and woodcutter William Morris complained about the coldness and poor legibility of the typefaces from Parma. Bodoni himself, as far as his typefaces were concerned, was not especially inclined towards any theories. He created what he considered to be beautiful and useful. His typography is determined by the maxim “A book becomes exemplary when the purity of the simple beauty of the type is most effective”.

The beginning of the industrial revolution in the early 19th nineteenth century led to different production requirements, and with that came an overproduction of goods. Typefaces from previous centuries were neither technically nor formally suitable for the large-format printing of product and services advertisements. Now headlines had to scream and mercilessly use up what little space there was. Fast steam-powered printing machines like the press for the Times (1814) enabled large editions to be printed quickly, but weren’t too gentle on the printed material. The platen presses in particular, first introduced by Isaak Adam in Boston in 1830, really damaged the fine lines of classicist typefaces.

Nonexistent serifs can’t break off, while bold serifs withstand printing better. Sans serif typefaces also take up less space while slab serif letters appear loud and impressive. The first sans serif typeface appeared in 1816 in a catalogue from the Caslon type foundry called Egyptian of all things. We actually use that term to describe slab serif typefaces, while Figgins still called a serif an Antique. The term Egyptian reflects the fashion of the time, as there had been a craze for all things Egyptian in England only a few years previously. In the Treaty of Amiens of 1802 Napoleon ceded Egypt to the British, who promptly sent the first pieces of booty from the Nile to London. Like every other fashion, it soon influenced the output of the type foundries.

Typography soon changed to fit the new advertisement typefaces. Simple pure beauty, as Bodoni had stipulated a few years before, was no longer in demand. Loudness, size, and variety were instead the order of the day. White space became expensive, sheets had to be crammed full of print up to the edges. Newspapers had narrow columns in order to squeeze many different topics onto one page, so narrower, more robust typefaces were cut for that purpose. Technology kept up with the increasingly diverse contents of printed material. Around 1829 Firmin Didot in Paris introduced the stereotype, a process of producing letterpress plates by making a mould of a complete page and then casting it in an alloy. The use of several casts made larger print runs possible and meant less wear for the original fonts. In 1838 Moritz Hermann von Jacobi invented galvanizing, with which artwork such as woodcuts could be “lifted” and then copied to make a durable block. Typographers now had to integrate illustrations into their pages because text and image were easily printable in one forme. The invention of the process block in 1840 made it possible to insert handwritten typefaces or company logos into the page for printing. Around the end of the century, the invention of the halftone screen by Meisenbach meant that photographs could also be reproduced.

Typography toward the end of the 19th century could graciously be called eclectic. Everything was technically possible, so everything that could be done was done. The Arts & Crafts movement arose in England as a reaction to the historicism of the Victorian era and the machine-made products of the Industrial Revolution. William Morris (1834−1896) founded the Kelmscott Press in Hammersmith near London in 1891 in order to produce high quality books. He designed some typefaces of his own because he found all of the existing ones too cold and insipid (see Bodoni). His Golden Type was inspired by the early Venetian printer Nicolas Jenson. The ornamentation followed mediaeval woodcuts. The handmade approach to materials and the simplicity of form influenced movements such as Art Nouveau, the Vienna Secession, the Deutscher Werkbund, and even Bauhaus. A new kind of book art also developed in Germany. Fritz Helmut Ehmcke (1878−1965) and Friedrich Wilhelm Kleukens (1878 – 1956) were young type designers before the First World War. They rejected both the ornate style of Art Nouveau and the late classicism that was equally prevalent at the time. Their idea of a modern, tidy typographic design was more akin to the ideal of the Renaissance. This outlook was shared by the most important teachers of type and typography, who were at the same time typeface designers. Walter Tiemann (1876 – 1951) taught at Leipzig, F. H. Schneidler (1882 – 1956) at Stuttgart, and Rudolf Koch (1876 – 1934) at Offenbach. Their ideas remained significant until after the Second World War.

Manufacturing techniques around this time determined both the design and production of type. Just one year after the Linotype, the Lanston Monotype hit the market, invented by Tolbert Lanston. It cast single letters and was operated by a keyboard. Typographic design was thus subject to the changing parameters of typesetting machines. New typefaces had to be designed that could match the technical requirements of the new machines as well as the prevailing fashions, which changed ever more regularly due to the increasingly shorter period between the design and production of type. The pantograph enabled engraved designs of any size to be duplicated from a draft, even if some aesthetic compromises had to be made. In the USA William Leavenworth constructed the first cutter for wooden type characters in 1834 to meet the huge demand for large wooden poster fonts used for billboards.

The first machine for engraving steel punches was patented by Lynn Boyd Benton (1844 – 1932) in 1885, just at the right time to develop the typefaces the market demanded. Monotype and Linotype were responsible for many reissues of classic typefaces which later served as drafts for the phototypesetting of the 1960s and the first generation of digital typesetting machines in the 80s. Times New Roman, the most famous of all Antiquas, was designed by Stanley Morison (1889 – 1967) and Victor Lardent in 1932 at Monotype in England. It was based on Plantin, which F. H. Pierpont had already designed in 1913, also for Monotype, and which in turn drew on Dutch Baroque typefaces of the 17th seventeenth Century.

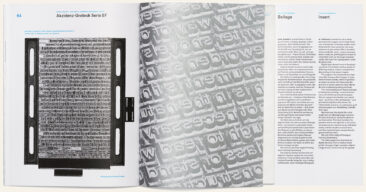

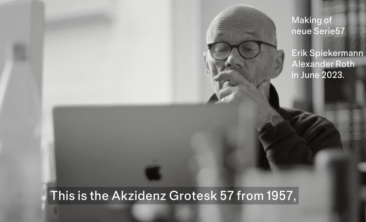

There was a new form of type being used at the start of the 20th twentieth Century, although it still played a minor role. To get a taste of how unusual and alien this new type seemed at the time, we need only note the description “Grotesk”, given to these typefaces on their first appearance at the start of the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th nineteenth Century. In the USA the sans serif typefaces were deemed equally strange, earning them the name “Gothic”. In Germany, Akzidenz Grotesk, first released in a single weight in Berlin in 1896, is regarded as the mother of its genre. Its roots are fairly obscure, but one of its siblings was Royal Grotesk, made in the 1880s at Ferd. Theinhardt. Meanwhile in the USA, in 1904, Morris Fuller Benton (1872 – 1948) created Franklin Gothic, which could be considered its American counterpart. Benton was responsible for many other classic typefaces including Garamond, Bodoni, Cheltenham, Century, News Gothic, Bank Gothic, Clearface, and Cloister.

Sans serif typefaces such as Akzidenz Grotesk and Franklin Gothic trace back to the classicist ideal. Univers, designed by Adrian Frutiger (1928 – 2015) and released in 1957, the first typeface to be systematically constructed and named as a family, also adheres to this model. Frutiger’s later design of a classicist Antiqua, Centennial, is therefore also a Univers with serifs.

The sans serifs from England conform to the Renaissance model, the best known being Gill Sans by Eric Gill (1882 – 1940) from 1928, which coined the term for these typefaces in English. It was only in the 90s that there was a major reemergence of sans serif faces, which — like FF Meta by Erik Spiekermann — recall Syntax by Hans Eduard Meier (1922 – 2014), released in 1969. In the Netherlands in particular this kind of typeface design is strongly encouraged. It is closely linked to the movement of the hand when writing, thereby creating rhythm and contrast. This direction is the most common among contemporary designs.

Sans serif typeface design can also be defined by its pure geometric forms. In the 1920s every major type foundry in Germany had such a Grotesk on offer. The most successful of these typefaces was Futura by Paul Renner (1878 – 1956), released by Bauer in 1928. Even though Futura exactly fit the kind of typeface for the modern age espoused by the Bauhaus representatives of Elementary Typography, it came out too late to be used for the school’s typesetting.

In the Twenties typography became an important discipline because it merged communication and expression. Dadaists like Kurt Schwitters didn’t set their work in cumbersome lead type, but made montages of prints, photos, and words on shreds of paper. On the other hand De Stijl in the Netherlands and Moholy-Nagy, Joost Schmidt, and Herbert Bayer of the Bauhaus used typefaces, colours and halftone images for book pages, catalogues, and posters. The artist El Lissitzky (1890 – 1941) was the Soviet cultural delegate in Weimar. There he developed his form of expression, the “typophoto”, and strongly influenced the Bauhaus colleagues and De Stijl. In 1925 a young Jan Tschichold (1902 – 1974) published an essay (using the first name of Iwan) in a special edition of ‘Typographische Mitteilungen’ (Typographic News) under the title ‘Elementary Typography.’ This was his manifest for a “New Typography“. In 1933 he emigrated to Switzerland whereupon he soon vehemently rejected the tenets of the New Typography. He returned to the traditional way, promoting the use of older Antiqua typefaces and the symmetric arrangement of page elements, which he had previously dismissed as outdated.

After the end of the Second World War, Swiss graphic design became the prevailing trendsetter, first spreading from Zurich to Germany and then throughout the world. The search for a rational and straightforward typeface led most graphic designers to Akzidenz Grotesk, cast and sold by Berthold in Berlin. The Haas’sche type foundry in Münchenstein had its Haas Grotesk on offer, which could be traced back to Scheltersche Grotesk by Schelter & Giesecke in Leipzig. Scheltersche was the font which lay in the cases at the Bauhaus workshops and in which much of the material was set that represented the eponymous style. It nevertheless didn’t quite match the expectations of designers who were looking for a typeface free of historical ballast and which didn’t push its way to the foreground.

The success of Akzidenz Grotesk prompted Eduard Hofmann, business director at Haas, to commission his colleague Miedinger to finalise sketches for a typeface that would compete in the same market. The Haas’sche type foundry belonged to D. Stempel AG in Frankfurt, which in turn was owned by Linotype. It was Stempel who suggested they find a popular name to help sell the new typeface. As there were sewing machines and an insurance company already using the name Helvetia (Switzerland), Hoffmann suggested Helvetica, meaning “Swiss”. It was released as Helvetica in 1957, the same year as Univers. That year also saw the Treaty of Rome and the Citroën DS.

The featureless typeface became world famous in the mid 60s, particularly as American businesses sought to lend themselves an air of modernity and cosmopolitanism by adopting it as their company typeface. It was no surprise then that it was an American who saw to it that Helvetica would become the standard typeface for the new tool of the graphic industry. In 1984 Steve Jobs selected the thirteen fonts to be installed on the first Apple laser printer. Among them Helvetica was the neutral, objective business font, with which one couldn’t go wrong.

The ironic thing is that most computers don’t have the original but the fake. In order to save license fees, Microsoft installed a clone in 1990 which has the same widths as Helvetica and – like all imitations – is formally inferior. But it can be found under the name Arial in all font menus and has thus become the most used system font.

The type foundries had already once reworked the classic typefaces for new typesetting systems. They had to do so again in the late 60s, when the first phototypesetting machines came on the market. The designs were no longer cut in steel and cast in lead, but drawn and transferred photographically onto carriers from which each letter was projected onto film. Seeing as the new material was not subject to any mechanical limitations, typeface designers were free from creative restrictions. Nowadays we can compare many of the 70s seventies typefaces with typography toward the end of the 19th nineteenth Century. The International Typeface Corporation ITC in New York did not only release many typefaces which reflected the spirit of advertising on Madison Avenue, they also had a new distribution model. Up until then all manufacturers of typesetting systems had their own type formats which wouldn’t work on their competitors’ machines. That gave graphic designers and typographers an incentive to favour one particular system because it exclusively offered certain fonts. At the same time it allowed many companies to prosper by either copying typefaces and selling poor imitations cheaply or altering them slightly and releasing them under different names. Now ITC delivered artwork to all manufacturers who paid license fees, and consequently these were the only fonts that were available on all machines.

Phototypesetting systems were still so complicated to use and so dear that a whole industry of layout typesetters emerged, selling their know-how at lucrative prices. At least the device operators were still skilled typesetters who had learnt the rules and would apply a certain standard to their intermediate product. Graphic designers, on the other hand, were keen to intervene and add their mark before sending the final artwork to the printers.

Phototypesetting fonts could be made to any size and placed in any position on a page by paper- or film make-up. The right angle was no longer all-important for the layout. For the design hippies of the flower power era this was excellent news.

The end of the design process always required a piece of film from which the printing plate was exposed. For this, apart from the typesetter, a reproduction photographer was required to capture the images on film, a lithographer or finished artist to copy together type and images for each individual colour, and graphic designers to have the ideas and specify layouts.

This mode of production became outdated virtually from one day to the next in the mid 80s eighties with the invention of Adobe’s page description language PostScript by John Warnock (1940 – 2023) and Chuck Geschke (1939 – 2021). This computer language allows every point on a page to be defined and marked to within a thousandth of a millimeter. Be it image, graphic element, or type, everything is composed of tiny pixels that are transferred to paper, film or printing plate by laser beam or ink jet.

The appearance of the Apple Macintosh along with the first laser typesetter by Linotype established desktop publishing, DTP. The job description of typesetters transformed into that of digital media designer. Graphic designers today no longer merely need to have ideas and visualize them, instead they are usually also responsible for the entire page, which they hand over ready to print and which goes to the printing plate without film exposure or any other final visual manifestation involved. The end of the division of labour meant that much expertise disappeared and new generations of designers had learn the rules all over again. A phase of deconstruction ensued in the mid 90s, when all the old rules were put into question without any new ones to replace them. Like punk in the 70s, the grunge movement of the time found its typographic expression in the wild splicing together of illegible spontaneous typefaces, blurry images and overlapping areas and backgrounds. Software such as Photoshop created the conditions in which the distinction between image and type could disappear.

Along with the liberation of page design from any kind of mechanical constraint, there’s the possibility of manipulating any of the fonts available in Postscript format. Now anyone can become a type designer, providing they can pay for one of the programs with which letters can be drawn and fonts produced.

Like in all previous phases of typographic history, after these developments it took a while for new rules to be developed (which surprisingly often turned out identical to the traditional ones) and readers and users of visual communications were put back into the focus of design activities. In the mid 80s the fonts for the new format were converted — initially by the traditional type manufacturers — without which no newspapers, magazines or books can be published. The first versions suffered from teething problems, and have since all been reworked.

Even young type designers couldn’t get enough of the new possibilities in the beginning. Graphic designers like Neville Brody or David Carson oriented their typefaces and layouts according to the Zeitgeist, erasing the separation of image and type. They painted digitally. In The Hague in 1990 Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum programmed the first typeface with a random generator that changed its outlines each time it was printed. Beowulf was the first random font, and its dirty edges were an antidote to the perfect but often soulless Postscript fonts. In 1986 the type designer Zuzana Licko from Berkeley used the rough pixels of early screen displays to make typefaces that merrily show off their crude outlines. She also ended up returning to the classics and designed her version of Baskerville under the name of Mrs Eaves – John Baskerville’s housekeeper. Well-established designers like Adrian Frutiger and Hermann Zapf oversaw the redigitalization of their old typefaces, while masters like Matthew Carter designed fonts for the computer screen on that medium. His Georgia is not only perfectly legible on screen but can also stand up to the classics as a proper text face.

In 1988, Erik Spiekermann started FontShop, the first independent distributor of fonts. They offered fonts from many freelance designers as well as small digital “foundries”. FontShop also curated their own label, FontFont, as “type for designers by designers”. His own FF Meta heralded the arrival of a new kind of sans serif which anticipated the trends of that decade and was called “the Helvetica of the 90s”.

The new distribution model enabled freelance type-designers to bring their own designs to market without the help (or interference) of large companies. Innovation now came mostly from those individuals who often had to support their typedesign activities with “normal” design work. This brought the design of typefaces closer to the normal practise of communication design, increasing type’s visibility and acceptance.

Nearly all major brands now have their own typefaces. Newspapers and magazines can have special typefaces designed for them which not only reinforce their brands but may be specifically tailored to suit production requirements such as paper or printing machines, and even match the readers’ habits and expectations.

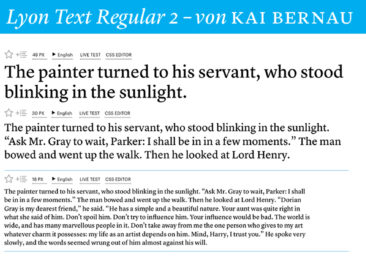

Huge font clans with over 144 members offer every kind of possible use, even for complex printing matter. Most new text typefaces are offered with at least seven weights, a feature enabled by software for interpolating between the thinnest and the heaviest weight. Variable fonts are the latest development, giving designers more choices than most can handle.

At the start of the 21st twenty-first century better tools exist than ever for the design of printed matter and other media. The differences between traditional book typography, functional design concepts and sophisticated, colourful advertisements are no longer the guiding factor, but rather the synthesis of these varying strands. Different typefaces may be mixed, justified type exists alongside ragged type, freeform page layout alongside strict grid systems. And for headlines, packaging, flyers and other forms of disposable printed matter, websites and videos, there are more than 250,000 typefaces that are sold or given away as fonts. And if it isn’t legible, it serves to boost the creative expression of its originators.

Technical possibilities today mean that anyone with a PC and a printer can be a typographer, programmer, typesetter, designer, lithographer, print technician, editor and corrector. Business has also changed together with production. Alongside the major manufacturers such as Adobe and Monotype – which has bought up every other successful digital foundry – there are now hundreds of tiny digital foundries that often have no more than a couple of fonts and a website. Everyone is in competition with one another, but almost everyone gets along. Google Fonts is another major player, offering “libre” fonts – you don’t pay a license fee, but Google gets a look at your font server data.

Designers have great choices: there have never been such useful tools for creating good typography. Nor so few excuses for doing something badly. ★

This article needs more illustrations. Not every reader will be able to visualize every typeface, machine or person mentioned.

I’ve added that to my list …